Why Exploring Space And Investing In Research Is Non-Negotiable

by Ethan Siegel October 26, 2017 (forbes.com)

• With all the suffering in the world — starvation, disease, persecution, and natural disasters — it is often asked, why should we spend public money on an enterprise like fundamental scientific research?

• A NASA rocket scientist named Ernst Stuhlinger responded to this question in 1970. Stuhlinger dreamed of a manned mission to Mars as early as 1958, and advocated for increased investment in science and exploration throughout his entire life. In 2008 he passed away, at the age of 94, as one of the last surviving members of Operation Paperclip. Stuhlinger said:

• – Goals of high challenge provide strong motivation for innovative work which serves as a catalyst for further lofty goals.

• – A mission to Mars, for example, would bring new technologies worth many times the cost of its implementation.

• – We need more knowledge in physics and chemistry, in biology and physiology, and very particularly in medicine to cope with all these problems.

• – We need more knowledge in physics and chemistry, in biology and physiology, and in medicine to cope with all these problems which threaten man’s life: hunger, disease, contamination of food and water, and environmental pollution.

• – We need new material and methods, to invent better technical systems, to improve manufacturing procedures, to lengthen the lifetimes of instruments, and even to discover new laws of nature.

• – Each year, about a thousand technical innovations generated in the space program find their ways into our earthly technology where they lead to better kitchen appliances and farm equipment, better sewing machines and radios, better ships and airplanes, better weather forecasting and storm warning, better communications, better medical instruments, better utensils and tools for everyday life.

• – Higher food production through survey and assessment from orbit, and better food distribution through improved international relations, are only two examples of how profoundly the space program will impact life on earth.

• – The space program is taking over a function which for three or four thousand years has been the sad prerogative of wars.

• – Traveling to the Moon and eventually to Mars and to other planets is a venture which we should undertake now. In the long run, space exploration will contribute more to the solution of the grave problems we are facing here on earth than many other potential projects.

• – This will become a better earth, not only because of all the new technological and scientific knowledge which we will apply to the betterment of life, but also because we are developing a far deeper appreciation of our earth, of life, and of man.

As vast as our observable Universe is and as much as we can see, it’s only a tiny fraction of what must be out there.

Around the country and around the world, there is no shortage of human suffering. Poverty, disease, violence, hurricanes, wildfire and more are constantly plaguing humanity, and even our best efforts thus far can’t address all of everybody’s needs. Many are looking for places to cut funding, ostensibly to divert more to humanitarian needs, and one of the first places that comes up in conversation is “extraneous” spending on unnecessary scientific research. What good is it to conduct microgravity experiments when children are starving? Why smash particles together or pursue the lowest possible temperatures when Puerto Rico is still without power? And why study the esoteric mating habits of endangered species when nuclear war threatens our planet? To put it more succinctly:

With all the suffering in the world — starvation, disease, persecution, and natural disasters — why should we spend public money on an enterprise like fundamental scientific research?

This is a line of thinking that’s come up repeatedly throughout history. Yes, it’s short-sighted, in that it fails to recognize that our greatest problems require long-term investment, and that society’s greatest advances come about through hard work, research, development, and often are only realized years, decades, or generations after that investment is made. Investing in science is investing in the betterment of humanity.

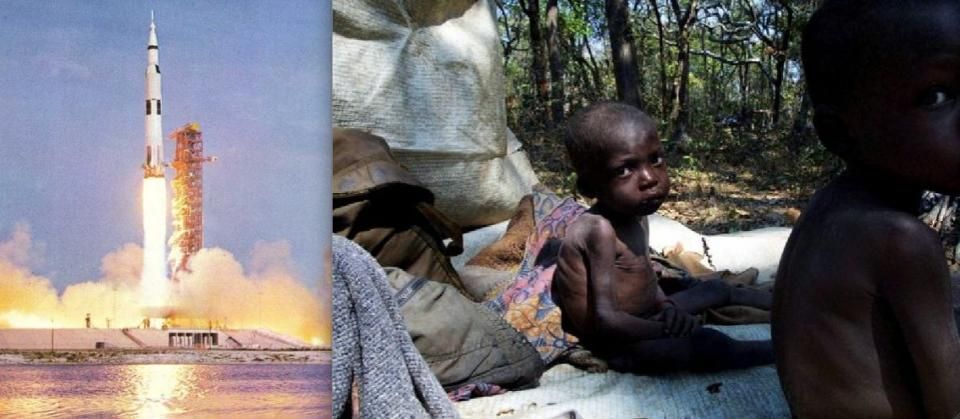

But that’s not always an easy path to see, particularly when suffering is right in front of you. Back in early 1970, shortly after the first Apollo landing, a nun working in Zambia, Africa, Sister Mary Jucunda, wrote to NASA. She asked how they could justify spending billions on the Apollo program when children were starving to death. If one pictures these two images side-by-side, it hardly seems fair.

To invest in any one thing means to not invest in something else, but both science/space exploration and humanitarian relief are worthy of the investment of human resources.

The letter somehow made it to the desk of one of the top rocket scientists at NASA: Ernst Stuhlinger. At the time, Stuhlinger, one of the scientists brought to the United States as part of Operation Paperclip at the conclusion of World War II, was serving as the Associate Director of Science at NASA. Facing an accusation of inhumanity must have been particularly painful for someone who was still often accused of being a Nazi for his role in the German rocket program, but Stuhlinger was unshaken. He responded by writing the following letter, reprinted in its entirety, below. (It’s long, and it only contained one picture, but it’s arguably even more relevant today than it was in 1970.)

Your letter was one of many which are reaching me every day, but it has touched me more deeply than all the others because it came so much from the depths of a searching mind and a compassionate heart. I will try to answer your question as best as I possibly can.

First, however, I would like to express my great admiration for you, and for all your many brave sisters, because you are dedicating your lives to the noblest cause of man: help for his fellowmen who are in need.

You asked in your letter how I could suggest the expenditures of billions of dollars for a voyage to Mars, at a time when many children on this earth are starving to death. I know that you do not expect an answer such as “Oh, I did not know that there are children dying from hunger, but from now on I will desist from any kind of space research until mankind has solved that problem!” In fact, I have known of famined children long before I knew that a voyage to the planet Mars is technically feasible. However, I believe, like many of my friends, that traveling to the Moon and eventually to Mars and to other planets is a venture which we should undertake now, and I even believe that this project, in the long run, will contribute more to the solution of these grave problems we are facing here on earth than many other potential projects of help which are debated and discussed year after year, and which are so extremely slow in yielding tangible results.

Before trying to describe in more detail how our space program is contributing to the solution of our earthly problems, I would like to relate briefly a supposedly true story, which may help support the argument. About 400 years ago, there lived a count in a small town in Germany. He was one of the benign counts, and he gave a large part of his income to the poor in his town. This was much appreciated, because poverty was abundant during medieval times, and there were epidemics of the plague which ravaged the country frequently. One day, the count met a strange man. He had a workbench and little laboratory in his house, and he labored hard during the daytime so that he could afford a few hours every evening to work in his laboratory. He ground small lenses from pieces of glass; he mounted the lenses in tubes, and he used these gadgets to look at very small objects. The count was particularly fascinated by the tiny creatures that could be observed with the strong magnification, and which he had never seen before. He invited the man to move with his laboratory to the castle, to become a member of the count’s household, and to devote henceforth all his time to the development and perfection of his optical gadgets as a special employee of the count.

The townspeople, however, became angry when they realized that the count was wasting his money, as they thought, on a stunt without purpose. “We are suffering from this plague” they said, “while he is paying that man for a useless hobby!” But the count remained firm. “I give you as much as I can afford,” he said, “but I will also support this man and his work, because I know that someday something will come out of it!”

Indeed, something very good came out of this work, and also out of similar work done by others at other places: the microscope. It is well known that the microscope has contributed more than any other invention to the progress of medicine, and that the elimination of the plague and many other contagious diseases from most parts of the world is largely a result of studies which the microscope made possible.

The count, by retaining some of his spending money for research and discovery, contributed far more to the relief of human suffering than he could have contributed by giving all he could possibly spare to his plague-ridden community.

The situation which we are facing today is similar in many respects. The President of the United States is spending about 200 billion dollars in his yearly budget. This money goes to health, education, welfare, urban renewal, highways, transportation, foreign aid, defense, conservation, science, agriculture and many installations inside and outside the country. About 1.6 percent of this national budget was allocated to space exploration this year. The space program includes Project Apollo, and many other smaller projects in space physics, space astronomy, space biology, planetary projects, earth resources projects, and space engineering. To make this expenditure for the space program possible, the average American taxpayer with 10,000 dollars income per year is paying about 30 tax dollars for space. The rest of his income, 9,970 dollars, remains for his subsistence, his recreation, his savings, his other taxes, and all his other expenditures.

You will probably ask now: “Why don’t you take 5 or 3 or 1 dollar out of the 30 space dollars which the average American taxpayer is paying, and send these dollars to the hungry children?” To answer this question, I have to explain briefly how the economy of this country works. The situation is very similar in other countries. The government consists of a number of departments (Interior, Justice, Health, Education and Welfare, Transportation, Defense, and others) and the bureaus (National Science Foundation, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, and others). All of them prepare their yearly budgets according to their assigned missions, and each of them must defend its budget against extremely severe screening by congressional committees, and against heavy pressure for economy from the Bureau of the Budget and the President. When the funds are finally appropriated by Congress, they can be spent only for the line items specified and approved in the budget.

The budget of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, naturally, can contain only items directly related to aeronautics and space. If this budget were not approved by Congress, the funds proposed for it would not be available for something else; they would simply not be levied from the taxpayer, unless one of the other budgets had obtained approval for a specific increase which would then absorb the funds not spent for space. You realize from this brief discourse that support for hungry children, or rather a support in addition to what the United States is already contributing to this very worthy cause in the form of foreign aid, can be obtained only if the appropriate department submits a budget line item for this purpose, and if this line item is then approved by Congress.

You may ask now whether I personally would be in favor of such a move by our government. My answer is an emphatic yes. Indeed, I would not mind at all if my annual taxes were increased by a number of dollars for the purpose of feeding hungry children, wherever they may live.

FAIR USE NOTICE: This page contains copyrighted material the use of which has not been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. ExoNews.org distributes this material for the purpose of news reporting, educational research, comment and criticism, constituting Fair Use under 17 U.S.C § 107. Please contact the Editor at ExoNews with any copyright issue.

Ernst Stuhlinger, future technology, space exploration